- leadership

- Blog post

Changing employee behavior: Social vs. financial incentives

You manage a team of six people, and they’re all good workers. But a couple of them aren’t as punctual as you’d like. In fact, they show up late for work at least three or four times a month.

So, figuring that money talks, you start thinking about monetary ways to handle the issue. You consider two alternatives. You could either punish frequent latecomers by reducing their annual bonuses, or reward folks who show up on time with a small supplement to their bonus.

Which is better? Unfortunately, they’re both likely to fail – because neither a financial incentive nor a disincentive is the right tool for what you’re trying to accomplish here.

Fines didn’t work

To see why, let’s look at a study from the University of Chicago involving the use of financial incentives. In this case, the researchers wanted to encourage parents to pick up their kids on time from a chain of daycare centers.

Most parents already did. And if they were late, it was rarely by more than half an hour. But if even a single parent was late, a staffer had to stay until the child got picked up. That cost the daycare centers money and frustrated staffers, who had their own obligations after work.

So the researchers conducted a test. At six of the centers, they instituted a small fine for any pickup more than 10 minutes late. At the remaining four centers, no fine was introduced. As expected, late pickups were unchanged at those centers.

But where a fine was imposed, tardiness increased immediately and kept going up. Eventually late pickups were twice as frequent as they’d been before the fine.

How could that be?

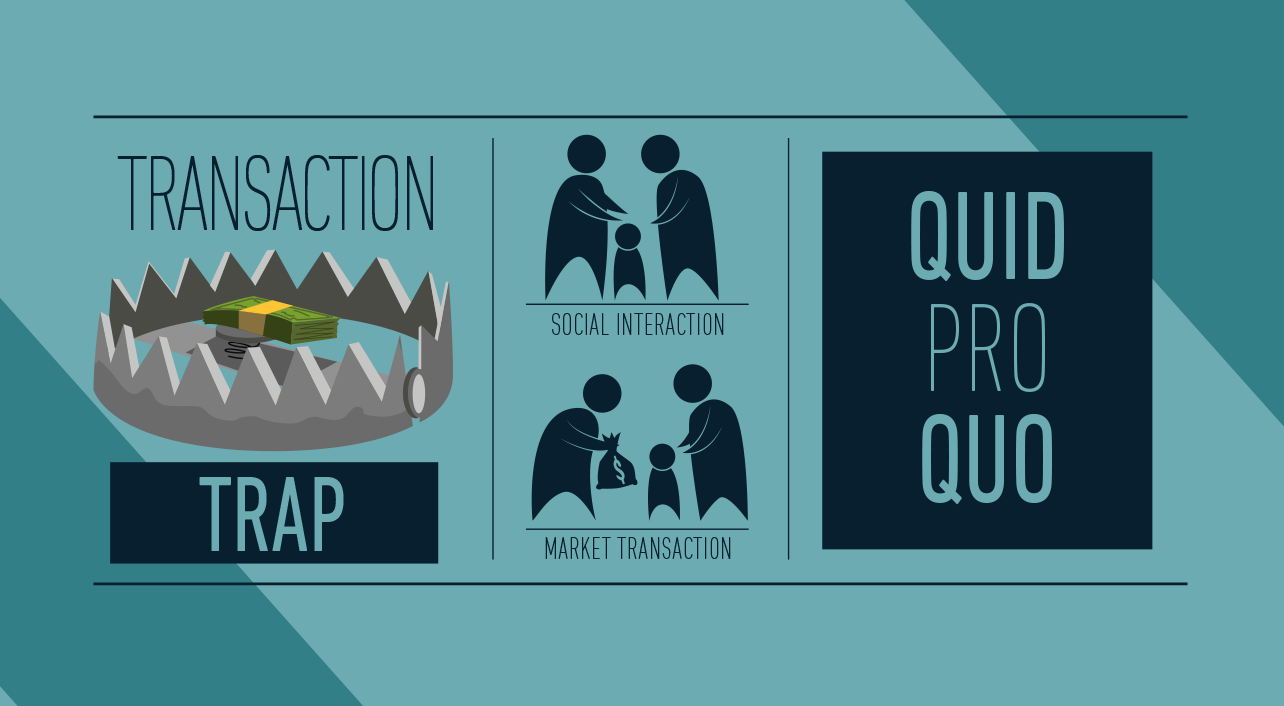

The ‘transaction trap’

Before, most parents had hurried to pick up their kids on time because of social pressure. They didn’t want to inconvenience the teacher or appear to be taking advantage.

The fine eliminated that pressure. It became a price parents could pay for squeezing in an extra half hour at the office.

The daycare centers had fallen into the transaction trap. They’d transformed a social interaction – one characterized by cooperation and trust – into a market interaction – one that is transactional, impersonal and based on quid pro quo.

Your attempts to get people to work on time will likely fail for the same reasons. Before, most people were showing up on time because it was a social expectation. But you’ve now made lateness into something people can buy: They can just “pay the fine” in exchange for coming in late. And it doesn’t really matter if you frame the incentive as a bonus or a fine – it amounts to the same thing.

Market or social interaction?

Now, there’s nothing wrong with market interactions in the right context – for example, when you’re setting performance-related incentives or negotiating salary. In those situations, people expect to be talking about money.

However, when you apply financial incentives to solve problems that primarily involve social interactions, they often backfire. Benefits such as cooperation and generosity are lost. Employees start seeking to maximize their gains – giving as little as they can for what they can get in return.

But here’s a sticky problem for managers: The distinction between social and market interactions can get fuzzy. If you give Rebecca a $50 gift card because she spent her weekend helping a customer with an emergency, is that a market interaction or a social interaction? Mostly the latter. Rebecca wouldn’t give up a weekend just to earn fifty bucks. She did it because it was the right thing to do. The gift card is a social signal – an acknowledgment of her effort and a way to say thank you.

Your plan to tackle lateness was different. You considered using money essentially as a bribe. So people could pass it up and still feel that they were being fair to you, the team and the company.

Research shows that social obligations usually have a greater influence over behavior than financial carrots and sticks. So you could tap into that power. You might say: “When you don’t show up on time, colleagues who depend on you feel you’re being disrespectful. You disrupt their daily planning and place an unfair burden on them.” That’s the truth, and it’s also a powerful incentive to do the right thing.

Making it work

Here are some other situations where you can leverage social interactions to get the behavior you want:

Meeting deadlines

Explain that when people miss deadlines, others have to work harder or faster to pick up the slack.

Noncooperation with other departments

Emphasize that noncooperation is bad for the company, and hurts the team because other departments will respond in kind.

Behavior in meetings

Remind people that when they talk over their colleagues, cut off discussion or push personal agendas, they’re disrespecting their colleagues.

Negativity

Before firing or disciplining people with bad attitudes, you might first frame the issue in terms of “social interactions” by telling them something like this: “Your sarcastic comments are hurting morale, and that’s making things harder for everyone on the team.”

This blog entry is adapted from the Rapid Learning module “Avoiding the ‘transaction trap’: When do financial incentives work – and when can they backfire?” If you’re a Rapid Learning customer, you can watch the video here. If you’re not, but would like to see this video (or any of our other programs), request a demo and we’ll get you access.

The blog post and Rapid Learning video module are based in part on the following research article: Gneezy, U. & Rustichini, A. (2000) A Fine Is A Price.” Journal of Legal Studies, University of Chicago. 29(1), 1-17.

Get a demo of all our training features

Connect with an expert for a one-on-one demonstration of how BTS Total Access can help develop your team.